Ex-FATA’s Justice Gap Keeps Centuries-Old Jirgas Alive and Trusted

Maaz Khan

On a chilly evening in Bajaur, dozens of men sit cross-legged on a carpeted courtyard, their turbans neatly tied, prayer beads in hand. The air is heavy with anticipation. Two families have arrived to settle a long-running land dispute. Instead of travelling to Peshawar’s crowded courts, they have come before the jirga—the centuries-old council of elders that has long served as the ultimate authority in the tribal belt.

Within hours, after hearing both sides, the elders deliver a verdict accepted by both parties. No paperwork, no legal jargon, no delays, and no hefty advocate fees—only reconciliation sealed with handshakes and cups of green tea.

Scenes like this remain common across Pakistan’s tribal districts, even after the merger of the erstwhile Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the wake of 25th Constitutional Amendment in 2018.

FATA was comprised of seven administrative units (Agencies), including Mohmand, Bajaur, Khyber, Orakzai, Kurram, North Waziristan and South Waziristan along with six Frontier Regions (FRs): FR Peshawar, FR Kohat, FR Bannu, FR Lakki Marwat, FR Dera Ismail Khan and FR Tank.

Following the constitutional reforms, both the tribal agencies and FRs were merged with their adjoining administrative divisions.

While the state promised modern courts, constitutional rights and access to justice, many locals feel those promises have fallen short. Cases drag on for years in formal courts, lawyers’ fees cripple poor families, and hearings require long, costly journeys to distant cities. For most residents, the jirga remains the only system that feels real, accessible, and trustworthy.

“Courts take 15 years to decide what a jirga resolves in a week,” says Malik Syed Jan, an elder from Khyber district. His words capture the frustration shared by thousands who had hoped the merger would bring speedy justice. Instead, they find themselves caught in a slow and alien judicial process.

For young people too, the disillusionment is growing. “We thought the new system would be fair,” says Muhammad Haris, a university student from Mohmand. “But all we got were delays and expenses. In the end, we realised the jirga is still closer to our lives.”

Even women, historically sidelined in these councils, see potential in the system if reformed. Zainat Bibi, a community worker in Bajaur, argues, “If women are given a seat at the table, the jirga could serve everyone. It’s faster, cheaper, and more humane than the courts.”

The Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR), which ruled the tribal belt for more than a century, denied locals access to Pakistan’s mainstream judiciary. Though often described as a “black law”, the FCR gave jirgas semi-legal recognition through the office of the political agent—the administrative as well as judicial head of the respective tribal agency. While oppressive in many ways, that era meant disputes were settled locally and quickly. With the FCR abolished, the formal court system was extended to the tribal districts. Yet, the infrastructure has lagged behind. Judges and lawyers are few, facilities are underdeveloped, and the process itself feels detached from the culture of the people.

Experts say this gap explains why jirgas continue to thrive. “Justice is not just about legal codes—it is about community trust,” says Dr. Yousaf Khan, a professor at the University of Peshawar. “The jirga works because it belongs to the people. It respects their traditions while restoring harmony.”

Experts say this gap explains why jirgas continue to thrive. “Justice is not just about legal codes—it is about community trust,” says Dr. Yousaf Khan, a professor at the University of Peshawar. “The jirga works because it belongs to the people. It respects their traditions while restoring harmony.”

Indeed, beyond resolving disputes, jirgas perform a deeper social function. They aim to reconcile rather than punish, to mend relations rather than sever them. A land feud might end not only with a boundary settlement but also with a shared meal, symbolising peace. This restorative spirit is something the formal legal system rarely delivers.

Still, the jirga is not without flaws. Critics point out its exclusion of women, lack of written records, and the possibility of bias when dominated by powerful families. For many, the solution is not to discard the jirga but to reform it. Advocates suggest giving jirgas a legal framework, documenting proceedings, and including educated individuals, women, and youth to ensure fairness.

Interestingly enough, the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), 1898—the principal procedural law that governs investigation, trial, and adjudication of criminal cases across the country—also provides a legal basis for Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) by empowering courts to refer cases for mediation, conciliation, or arbitration as a means of out-of-court settlement.

The people of the tribal districts have lived through two contrasting realities: the authoritarian FCR era and the sluggish, costly judicial system after the merger. Between the two, the jirga continues to stand as a trusted middle ground. It is not perfect, but it is immediate, familiar, and rooted in culture.

As Pakistan seeks to build peace and stability in its former tribal belt, ignoring the jirga would mean ignoring the heartbeat of its people. Reviving and reforming the jirga system could bridge the gap between tradition and modernity, offering justice that is not only delivered but also felt. In the dusty courtyards and village hujras of the tribal districts, the jirga remains alive—and, for many, it remains justice itself.

Soldiers and citizens together overcome the flood crises in KPK

Laila Sadaf

In mid-August 2025, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) faced one of its darkest hours. Torrential rains, cloudbursts in mountain valleys, flash floods, and landslides struck Buner, Swat, Shangla, Mansehra, Bajaur, Battagram, and Lower Dir in rapid succession. Homes collapsed, roads vanished under water, and bridges crumbled, leaving entire communities cut off. Scores of people died; many more were missing or displaced. Yet amid this devastation, a story of courage and unity emerged—soldiers and citizens working side by side to confront a disaster that seemed overwhelming.

The scale of destruction was staggering. In Buner alone, more than 200 people lost their lives. In Mansehra, Swat, Shangla, and Bajaur, thousands of families were affected as landslides and raging torrents swept through villages. Remote valleys were left inaccessible, worsening the suffering of those stranded.

Amid this chaos, the Pakistan Army stepped in. Acting on directives from Chief of Army Staff Field Marshal Asim Munir, units across KP mobilised to assist in relief and rehabilitation. The Corps of Engineers took on the critical task of repairing broken infrastructure. Where bridges could not be restored immediately, temporary crossings were built to reconnect cut-off communities. Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) teams and K-9 units scoured debris for survivors, while Army aviation helicopters ferried stranded families to safety and delivered food, medicine, and essentials to areas unreachable by road. Medical units set up field camps, treating injuries and addressing outbreaks of waterborne diseases.

In areas like Mansehra and Bajaur, the disaster struck with ferocity. Swollen torrents swept away homes, farmland, and communication lines. Rescue efforts were carried out jointly by soldiers and locals who braved the floods to recover survivors and restore basic links. In villages perched along riverbanks, entire settlements were washed away. Yet local communities did not wait passively. Villagers dug through collapsed roofs, improvised rafts to evacuate families, shared food and blankets, and carried the injured to safer ground. Their knowledge of terrain proved invaluable in guiding Army teams through inaccessible zones.

Restoring connectivity became a lifeline. Army engineers erected temporary bridges, while villagers provided labour and materials to clear debris and lay footpaths. These improvised solutions meant the difference between isolation and survival—enabling medical care, food delivery, and evacuation of children and the elderly.

The coordination between military and civilian disaster units further amplified relief. USAR teams, aviation squads, and engineers worked alongside the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA), Rescue 1122, local volunteers, and NGOs. The PDMA declared emergencies, collected casualty data, and managed relief camps, while the NDMA coordinated federal support. Despite poor weather and treacherous terrain, more than 6,900 people were rescued, over 6,300 treated at medical camps, and nearly 600 tonnes of rations distributed. Roads were cleared in fragments, allowing convoys to reach deeper into affected areas.

The work was not without risks. In some valleys, heavy rains and landslides prevented even helicopters from reaching those in need. Rescue operations at night were dangerous, and some soldiers and relief workers lost their lives in service. Yet despite these challenges, the joint effort of disciplined troops and courageous citizens saved thousands from certain tragedy.

The work was not without risks. In some valleys, heavy rains and landslides prevented even helicopters from reaching those in need. Rescue operations at night were dangerous, and some soldiers and relief workers lost their lives in service. Yet despite these challenges, the joint effort of disciplined troops and courageous citizens saved thousands from certain tragedy.

In Mansehra, survivors recalled how neighbours opened their homes to the displaced and shared meagre supplies of food. In Bajaur, locals used bamboo planks and rafts to cross rivers until temporary bridges arrived. These acts of solidarity were as vital as official rescues.

The recovery phase has now shifted focus toward rebuilding with resilience. Army and civil engineers are working together to redesign bridges, strengthen embankments, and improve early warning systems. Local governments are distributing compensation, rebuilding homes, and planning permanent road and bridge reconstruction. The Army’s decision to donate one day’s salary from all personnel, along with over 600 tonnes of rations, symbolised a message of national unity—that every Pakistani has a role in overcoming the crisis.

The floods have left scars across KP, with livelihoods destroyed and infrastructure in ruins. But they also rekindled a spirit of solidarity, proving that soldiers and citizens together are stronger than disaster. As rebuilding begins, the province’s future resilience will depend on preserving this unity, strengthening local capacities, and investing in infrastructure that can withstand the next storm. When calamity returns, as it inevitably will, the people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa will be more prepared—and more united.

Floods Reveal Governance Failures in Combating Climate Challenges

Salman Ahmad

Once known as the land of rivers and mountains, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) now boasts dangerous terrain. August 2025’s dreadful floods, which claimed 228 lives in Buner alone, are a sobering reminder of government shortcomings that have let natural risks escalate into full-fledged disasters. The government’s assertion that a “cloudburst” was the cause of the disaster has already been denied by scientists and experts. Former Chief Meteorologist Mushtaq Ali Shah rejected the cloudburst story as scientifically untrue, explaining that the catastrophe was caused by the unusual collision of two meteorological systems over Malakand Division, which produced record rainfall. He cautioned that mislabelling catastrophes detracts from genuine policy solutions in addition to confusing the public. The true problem is on the ground below, where the province has lost its natural defences due to rampant deforestation, encroachments, and poor management.

The environmental context of KP makes its vulnerability more acute. With 27,000 hectares lost yearly, Pakistan’s forest cover has fallen to a dangerously low 5%. In KP and Gilgit-Baltistan, private and public forests are being cut down carelessly, trees are being removed from watershed areas, and construction is spreading out unchecked along riverbeds. As a result, the landscape is unable to control or absorb heavy rainfall. Bare slopes now speed up runoff, transforming seasonal downpours into deadly torrents where once dense forests served as natural sponges. Illegal housing and commercial development on floodplains in northern KP exacerbate the issue and are sure to cause disaster when swollen rivers eventually retake their path. Unlike other countries, where deforestation is partly offset by regrowth, Pakistan faces depletion without replenishment. This imbalance magnifies every storm, every landslide, and every flash flood.

However, blaming climate change alone would absolve governance shortcomings. Undoubtedly, climate change has a role. As the atmosphere warms, more moisture is retained, increasing the likelihood of heavy rains and flash floods. Northern glaciers are melting more quickly, increasing river levels and causing floods from glacial lake outbursts. However, climate shocks only expose the long-hidden effects of poor governance. The true scandal in KP is the breakdown of systems intended to alert, prepare, and safeguard communities. Villagers in Swabi expressed dissatisfaction over the lack of prior notice. District officials lack the ability—or the desire—to implement the forecasts issued by the Pakistan Meteorological Department. Roads had been washed away, making it impossible for ambulances and other equipment to reach the affected areas, and rescue efforts were left to locals excavating with their bare hands. Once more, the public was left to fend for themselves, and the government’s response was both inadequate and too late.

Laws like the River Protection Act, which forbid building along riverbeds, are disregarded with impunity. People and the government lack trust as a result of policymakers ignoring local customs and community structures that could have been used to promote compliance. The military is frequently called in during disasters, but the use of ad hoc interventions shows how inadequate civilian disaster management capabilities still are. Even though the National Disaster Management Authority acknowledges that house collapses account for almost one-third of flood fatalities, unsafe construction is still allowed to continue. On paper, there are building regulations, but they are not consistently enforced and are corrupt.

Laws like the River Protection Act, which forbid building along riverbeds, are disregarded with impunity. People and the government lack trust as a result of policymakers ignoring local customs and community structures that could have been used to promote compliance. The military is frequently called in during disasters, but the use of ad hoc interventions shows how inadequate civilian disaster management capabilities still are. Even though the National Disaster Management Authority acknowledges that house collapses account for almost one-third of flood fatalities, unsafe construction is still allowed to continue. On paper, there are building regulations, but they are not consistently enforced and are corrupt.

The floods in 2022, which covered a third of Pakistan, should have been a turning point. That disaster forced eight million people to leave their homes and caused more damage than the one in 2010. Three years later, though, KP is still not ready. The province has been muddling through with patchy, donor-driven projects that fall apart when the money runs out, instead of making early warning systems stronger, building infrastructure that can withstand disasters, and moving vulnerable communities. Monitoring of glacier lakes is not complete, community drills are not always held, and floodplain encroachment is still happening. A 2025 timber scam worth Rs1.7 billion exposed how deep corruption runs within forest management. In this situation, even good climate policies don’t make sense. The provincial government led by the PTI did come up with a climate change policy that fits with the national framework from 2021, but progress has not been steady. Ambitious goals, like mapping glacier lakes, making ecological corridors, and going after timber mafias, are either not being fully met or are being blocked by powerful groups with a stake in the outcome.

Flood-related deaths and increased public health costs are two indicators of the effects. Malaria, dengue, and diarrheal illnesses are expected to rise sharply as floods worsen and water quality deteriorates, according to the KP health department’s Climate and Health Adaptation Plan. A 20% increase in patient volume is predicted to put hospitals at risk of going over their current resource limit. A less obvious but no less destructive layer of the fallout is added by mental health crises, which include spikes in stress, anxiety, and depression. Another aspect of climate change is heatwaves, which are occurring earlier and more intensely in KP each year. Record-breaking temperatures are upsetting daily life, livelihoods, and agriculture. Once written off as a remote threat, climate change is now determining KP’s survival rhythms.

What should be done? The science is clear: protecting downstream communities depends on maintaining forests in mountain headwaters. However, preserving forests cannot be boiled down to token plantation campaigns. It calls for community-based forest management that empowers rather than alienates locals, independent monitoring, and law enforcement against timber mafias. Flood control needs to be rethought in a way that goes beyond temporary fixes. Resilient evacuation routes, permanent communication infrastructure, and district-level early warning systems are crucial. Families must be moved from riverbeds to safer areas and given housing options that take into account social and cultural realities, all while strict building regulations are enforced. Because communities stuck in survival economies are more likely to deforest and build on floodplains in a state of desperation, poverty alleviation and livelihood diversification are essential.

Climate governance at the provincial level needs to transition from rhetoric to action. Climate adaptation is frequently underfunded and dependent on outside assistance because it clashes with other priorities. While international partners can provide assistance, local accountability and ownership cannot be compromised. Above all, policymaking must no longer be a top-down process. Everyone in KP must participate in decision-making, training, and implementation, from the farmers of Swat to the craftspeople of Charsadda. No system will work and no law will be upheld without community involvement.

Buner and Swat’s August floods weren’t merely a result of nature. Decades of deforestation, careless building, and state neglect resulted in their creation. Pakistan will continue to be put to the test by climate change, which will bring longer heatwaves, more intense floods, and harsher storms. But if governance steps up to the plate, disasters don’t have to turn into tragedies. In 2010, 2022, and now in 2025, the alarm has been raised numerous times. Whether KP leaders will finally pay attention is the question. The province will continue to be caught in a deadly cycle where each monsoon brings destruction rather than relief unless there is sustainable planning, improved management, and the guts to take action.

Healing The Wounds of Conflict Through Relief & Rehabilitation in Bajaur & Beyond

Hassan Sajid

Peace is fundamental prerequisite for a nation’s socio-economic and political growth. Unfortunately, the wave of recent insurgency has once again threatened stability and security of Pakistan, especially of KP. It remains one of the gravest concerns for internal security, as well as socio-economic and political stability of Pakistan, jeopardising the livelihoods of thousands of people and forcing them to abandon their homes and assets across various areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, recently in Bajaur.

TTP and other extremist groups, emboldened by transnational outfits such as Islamic State, continue to operate through Bajaur, challenging the writ of the State and fostering an environment of fear. According to the Global Terrorism Index 2025, Pakistan is currently the world’s second-most terrorism-affected country, after Burkina Faso. Terrorist attacks in Pakistan doubled from 2023 to 2024, rising from 517 to 1,099. These militant groups are seen harassing the locals and receiving a fixed amount of extortion money from small businesses.

In regard to exploring the root cause of terrorism in Pakistan, it can rightly be said that the prevalent resurgence of militancy is not a cause but a consequence of more fundamental structural failures, such as persistent poverty, poor governance, political illiteracy, youth bulges and religious extremism, prevailing across the region, which serves as cultivated ground for the proliferation of terrorism. Bajaur in Erstwhile FATA is the most appropriate examples of such failures. Amnesty International revealed that scores of residents of FATA were being held in detention on suspicion of abetting and providing safe havens to the militants.

Thus, the recent wave of militancy and the military operation SARBAKAF against it have forced thousands of families into displacement. As the operation continues, the relief and rehabilitation efforts remain vital to heal the wounds of local people, restore national integrity and rebuild hope for socio-economic prosperity. In the same spirit, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government and Provencial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) are providing large-scale emergency relief and cash assistance to the displaced families. For that, the authorities have quickly organised a registration drive through which 50,000 – 75,000 one-time cash grants were provided to meet their immediate needs.

Thus, the recent wave of militancy and the military operation SARBAKAF against it have forced thousands of families into displacement. As the operation continues, the relief and rehabilitation efforts remain vital to heal the wounds of local people, restore national integrity and rebuild hope for socio-economic prosperity. In the same spirit, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government and Provencial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) are providing large-scale emergency relief and cash assistance to the displaced families. For that, the authorities have quickly organised a registration drive through which 50,000 – 75,000 one-time cash grants were provided to meet their immediate needs.

Additionally, camps and temporary shelters were established for the displaced people as the first-line relief mechanism. Government-run camps, notably the Bajaur Sports Complex, plus the vicinity of schools and other government buildings have been used to shelter displaced families while registration and relief distribution are carried out in the meantime. The government and security forces are actively responding to the plight of people, ensuring a prompt disposal of relief and rehab. Similarly; responding to the issue of limited registration centers, Bajaur’s district administration has recently set up another registration point in Utman Khel for affected families and promised to establish more centres on need base.

Moreover, authorities have already returned and rehabilitated families in the cleared areas. As security forces clear localities from militants’ presence and create an environment of peace, authorities have allowed residents to return to their homes. Moreover, they are committed to additional support including a second cash disbursements on their return. Repairment of schools, hospitals and livelihood support to prevent protracted displacement is also part of rehabilitation plan.

Hence, it can rightly be said that the scars of conflict in Bajaur are deep, but they are not beyond healing. Relief and rehabilitation efforts, though challenged by scale and resources, reflect the resilience of the people and the determination of the State’s security forces to restore peace and stability. Through immediate relief, he government and local authorities are laying the foundation for sustainable recovery. Yet, the true test lies not only in the reconstruction of infrastructure but also in the restoration of trust, dignity, and hope among the people. Bajaur’s story is a reminder that peace cannot be secured by military means alone; it must be nurtured through inclusive governance, social justice, and economic opportunities. Only then can the wounds of conflict be healed, not just in Bajaur, but across all regions struggling under the shadow of militancy.

From Merger to Marginalisation: Seven Years On, Promises Still Unfulfilled

Ghulam Dastageer

On May 25, 2018, President Mamnoon Hussain repealed the Frontier Crimes Regulations (FCR) through the FATA Interim Governance Regulation (FIGR), a transitional framework to govern FATA until full integration. On May 31, 2018, the 25th Constitutional Amendment was enacted, formally merging FATA with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The seven agencies and six FRs became tribal districts under KP’s jurisdiction, marking the end of FATA’s distinct administrative identity.

Seven years after the merger of the FATA with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa through the 25th Constitutional Amendment, large parts of the region still remain in a state of administrative limbo.

While some institutional reforms have taken shape, persistent gaps in judicial access, police coverage, education, health services, and civil bureaucracy continue to undermine the promise of equal citizenship for the people of the newly merged districts.

Judicial Reforms

The colonial-era FCR was formally abolished in 2018, with Political Agents and Assistant Political Agents replaced by Deputy and Assistant Commissioners, respectively. The judicial system was extended in principle, but in practice, most courts remain non-functional.

According to the UNDP’s Rule of Law Programme, approximately 229 judges, lawyers, and judicial support staff—one-third of them women—have been trained to operate in the merged districts. Despite this, the absence of operational courtrooms and public access has left traditional jirga systems as the default mechanism for dispute resolution in most areas. In most of the merged districts, the courts just exist in the district headquarters, while there is no presence of courts at the tehsil level.

Policing Infrastructure

Among the more visible reforms post-merger has been the expansion of formal policing. In March 2019, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government approved the establishment of 25 police stations across the seven merged districts and six former frontier regions. These included three stations each in Khyber, Mohmand, Kurram, North Waziristan, and South Waziristan. Two each in Bajaur and Orakzai. One each in Darazinda, Jandola, Hassankhel, Dara Adamkhel, Wazir, and Bhittani areas.

The first fully functional police station in Wana, South Waziristan, was inaugurated in May 2019, marking a symbolic shift in local law enforcement. More recently, on November 7, 2024, five model police stations were launched in Bajaur, Kurram, Mohmand, North Waziristan, and Orakzai. These facilities—equipped with gender-responsive desks, community halls, and modern amenities—were developed with funding from the Government of Japan and implemented by UNDP in partnership with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa police.

The first fully functional police station in Wana, South Waziristan, was inaugurated in May 2019, marking a symbolic shift in local law enforcement. More recently, on November 7, 2024, five model police stations were launched in Bajaur, Kurram, Mohmand, North Waziristan, and Orakzai. These facilities—equipped with gender-responsive desks, community halls, and modern amenities—were developed with funding from the Government of Japan and implemented by UNDP in partnership with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa police.

The KP government has also retrained and integrated over 2,000 Levy and Khasadar personnel into the provincial police system, who lack the basic know-how of policing. District-level policing plans have reportedly been prepared, though these remain largely undisclosed and unimplemented.

This modest expansion raises serious questions about capacity: Can a region of more than 27,000 square kilometres—plagued by militancy, tribal conflict, and cross-border infiltration—be effectively policed with just 25 stations? By comparison, settled districts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa often operate with dozens of police stations, supported by supervisory and investigative units.

Civil Administration

With the replacement of Political Agents by deputy commissioners, the civil administrative framework of the merged districts has been brought in line with the rest of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Yet, the rollout of provincial governance remains hampered by under-resourced offices, staffing shortages, and frequent budgetary delays. Despite formal restructuring, meaningful provincial integration and service delivery are still struggling to take root. For instance, the office of the Deputy Commissioner of the Khyber tribal district still operates from Peshawar.

Health and Education

According to recent reports, 5,826 State-run schools currently exist in the merged districts—of which 87 per cent are functional, while 775 remain non-functional. Despite this sizable footprint, no new school construction has been officially documented post-merger. This raise concerns that educational access in the region has not meaningfully expanded—only been maintained at best.

The high number of out-of-school children, particularly girls, combined with poor school infrastructure and a lack of trained teachers, suggests that institutional development in education remains stalled at a foundational level.

Seven years into the merger, the reality for residents of the merged districts remains one of unmet expectations. The structural transformation envisioned by the 25th Amendment remains incomplete. Without a substantial boost in institutional capacity, funding, and political will, the promise of integration and equality for the people of the former FATA remains more theoretical than real.

The Way Out

Despite the formal end of FATA’s colonial legacy through constitutional means, a growing number of residents across the merged districts believe that genuine integration remains elusive. Disillusionment with the law-and-order situation is deepening, particularly in Bajaur, North and South Waziristan, and Khyber, where militancy has resurfaced in recent months.

The perception of security rollback, rather than consolidation, has raised fears that the region may once again be subjected to a governance vacuum.

However, any attempt to reinstate the former FATA-like administrative system—even in a limited form—would likely face fierce public opposition. Across tribal districts, there is a growing consensus that reversing the merger would be unacceptable. Movements such as the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) have already mobilised public sit-ins (pasoons) and street protests to defend the hard-earned constitutional gains. Many see these forums as the last resort to resist any backsliding into non-democratic governance.

Among locals, there is a widely held belief that the Pakistan Army is behind the push for administrative reversal, allegedly motivated by control over mineral-rich lands. The slogan “jahan wasail hain, wahan masail hain” (where there are resources, there are problems) is increasingly voiced at public meetings, reflecting a deep mistrust towards the military’s intentions in the region.

If this perception is not addressed, resentment towards the Army could intensify, undermining its standing not just in tribal districts but across the Pashtun belt.

The situation could further deteriorate if the federal government considers introducing a 27th Constitutional Amendment that designates mineral-rich areas as federally administered territories, potentially removing them from provincial jurisdiction.

While such a move might serve fiscal or strategic goals—such as boosting federal revenues or defence allocations amid rising tensions with India—it would severely damage civil-military relations and could ignite a popular backlash, particularly among youth who now wield social media as a potent political and propaganda weapon.

Crucially, the failure lies not with the merger model itself, but with the incomplete implementation of the Sartaj Aziz Committee’s recommendations. For instance, the proposed three per cent share of the NFC Award, meant to fund development in merged districts, has yet to materialise.

From a political standpoint, any reversal would face stiff resistance in Parliament. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI)—now positioned as an anti-establishment party—retains a significant support base in ex-FATA and would likely oppose any constitutional regression.

Similarly, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) has categorically stated that it would not support any rollback of the merger, and its cooperation is essential for achieving the two-thirds parliamentary majority required for constitutional amendments.

At this critical juncture, the only viable way forward is a renewed political consensus that fully honours the original vision of integration. That means operationalising judicial and policing systems at the grassroots, completing infrastructure rollout, ensuring proportional development funding, and most importantly, restoring public trust through transparency and accountability.

Any effort to sidestep these imperatives would not only derail the merger process—it risks reopening wounds that Pakistan has worked so long and hard to heal.

Alarming Trend of Drone Attacks on Security Forces in KP

Shahzad Masood Roomi

Once known for guerrilla warfare and suicide bombings, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, a.k.a. Fitna-Al-Khawarij (FAK), has now embraced the modern tactic of using commercially available quadcopters, equipped with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), against security forces in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). A series of such attacks have been reported in KP’s southern districts, particularly in Bannu and adjacent merged areas. So far, at least eight such incidents have been confirmed during the past few months, including an attack on a police station in Bannu that resulted in the death of a woman and injuries to three children. Despite inaccuracies in many of these strikes, these incidents represent a dangerous scenario posing escalation, given the lack of necessary detection and countering drone capabilities of the local police force, such as anti‑drone sensors or jammers. Provincial police chief Zulfiqar Hameed’s admission that “the militants are better equipped than we are” underscores the widening technological disparity between police and the terrorists.

On May 19, 2025, a drone strike in Hurmuz village of Tehsil Mir Ali in North Waziristan, carried out by TTP, resulted in the killing of four children and provoked protests and sit-in demonstrations demanding accountability and an independent investigation. This is yet another ugly facet of FAK’s strategy. Kill innocents, blame the Pakistan Army and get more recruitments after displaying sympathy to the affected families. Security forces officially denied any involvement in the Hurmuz incidents and clarified that it was an act of terrorism by the FAK, yet some locals demanded clarity and justice amid escalating anger. In a separate incident in March 2025, a FAK drone strike in Katlang Tehsil of Mardan district killed nine members of a sheepherder family. The incident triggered provincial government enquiries and compensation pledges, despite security forces’ clarification that no drones were used by them. The announcement of compensation was exploited by FAK recruiters. This incident showcases the added complexities that FAK’s evolving drone tactics have introduced into ongoing counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations. It underscores the urgent need for new civil-military coordination mechanisms to effectively respond to these emerging threats.

Groups like the Hafiz Gul Bahadur’s and Lashkar-e-Islam are believed to have been testing DJI quadcopters equipped with 400–700g Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) since early 2024. Analysts note that this new drone-based approach represents not only tactical adaptation but also cross-conflict learning mirroring developments in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and among Afghan Taliban and ISIL affiliates. Such weapons provide the ability to strike from above without direct engagement, creating a force multiplier for non‑state groups.

Drones are not only used for direct attacks, but they also enable FAK to get real-time tracking of security forces’ movements. Now, it is an alarming fact that in KP, nearly 98% of FAK attacks in early 2025 were concentrated in KP’s tribal and southern districts, where drone activities were reported constantly. This aerial capability dramatically complicates counterterrorism strategies. In February and March 2025 alone, TTP carried out 147 attacks across the country, resulting in the deaths of 85 civilians and security personnel, with police among the most targeted groups.

Drones are not only used for direct attacks, but they also enable FAK to get real-time tracking of security forces’ movements. Now, it is an alarming fact that in KP, nearly 98% of FAK attacks in early 2025 were concentrated in KP’s tribal and southern districts, where drone activities were reported constantly. This aerial capability dramatically complicates counterterrorism strategies. In February and March 2025 alone, TTP carried out 147 attacks across the country, resulting in the deaths of 85 civilians and security personnel, with police among the most targeted groups.

The same period witnessed the deadliest monthly toll of militant strikes since 2014, with 228 fatalities recorded in March alone, including 73 security personnel. These grim statistics underscore how the emergence of airborne threats further strained the already overburdened police and frontier forces. The acquisition of drone capability by FAK poses grave strategic, operational and psychological challenges.

Strategic Surprise: Drones enable FAK to bypass perimeter defences and hit some important installations or convoys carrying VIPs.

Psychological Warfare: Unseen but lethal drones can create chronic fear, forcing fatigue among police and civilians alike, eroding morale and public confidence.

Civilian Endangerment: As has been discussed earlier, FAK is using drones against KP civilians to get fresh recruits and local support against security forces.

Operational Fragmentation: Security coordination becomes more complex when aerial threats intersect with military drone campaigns and joint counterinsurgency operations.

Countering this threat requires immediate multi-pronged measures. First, police outposts in vulnerable districts must be equipped with drone detection systems, jammers, or interception tools, and officers trained as drone spotters. Second, counter‑drone protocols and real‑time intelligence sharing must be established between civilian police and military air assets to ensure unified airspace control. Third, regulatory frameworks must restrict legal drone acquisition or flight in high-risk areas, with enforcement against unauthorized operators. Additionally, public awareness campaigns should educate civilians about drone warning signs, safe evacuation, and prompt reporting. Finally, intelligence cooperation with Afghan authorities and international partners is vital to trace supply lines of drone hardware and explosives, and disrupt training networks supporting militant drone deployment.

No Peace Without Military Strength in KP

Dr. Sahibzada Muhamma Usman

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has seen too many cycles of violence. The province, especially places like Bajaur near the Afghan border, has been caught in the middle of insurgency for years. Every time there is a lull, groups like the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) find ways to regroup. That’s why the State keeps going back to the same conclusion: without military strength, there’s no chance of lasting stability here.

Take account of the recent Operation Sarbakaf. Launched in August 2025, it is the latest reminder that the fight is still very real. Security forces, backed by artillery and helicopter gunships, went after militant hideouts in Bajaur. Also, reports say several militants were killed and captured. It was not a token of force; it was a clear attempt to dismantle a network that’s been haunting the region for years.

Notably, Bajaur’s geography makes it a natural entry point for militants’ crossing over from Afghanistan. The mountains and difficult terrain have given them cover for decades. So, when the army moves in with heavy weapons, it is not overkill. It’s a response to how deeply entrenched these groups are.

Of course, these operations come with a human cost. Some tribal elders have voiced worries about people being displaced again, which is fair. The memory of entire communities uprooted during earlier operations is still fresh. Nobody wants to relive that.

But there’s another side to it. KP’s Chief Minister Ali Amin Gandapur recently said, “The public and all institutions must work together to establish peace. Our future depends on it.” That’s the truth. The military can clear an area, but unless people and institutions back the effort, the militants just slip back in.

One of the toughest parts of this whole problem is that the TTP isn’t operating in a vacuum. They’ve got safe havens across the border in Afghanistan. Studies published this year point out how these sanctuaries are being used to regroup and plan attacks inside Pakistan. So even if Bajaur is cleared, the threat isn’t gone.

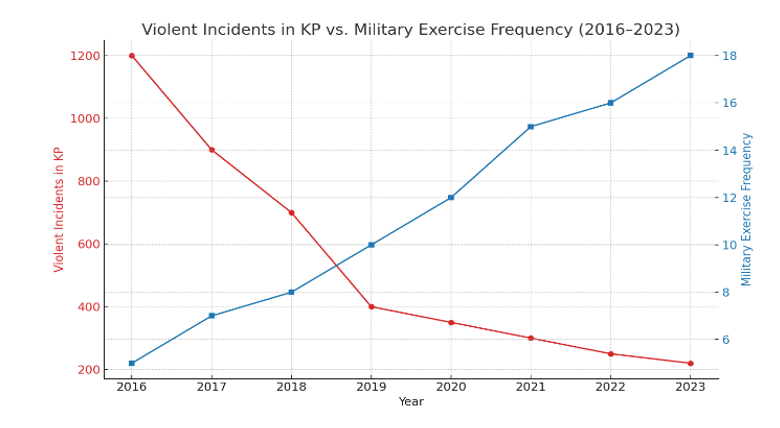

Notably, no peace without military strength in KP is possible. This is reflected in the graph below, which is synthesised from multiple credible resources.

Figure 1

Violent incidents in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) declined sharply as the frequency of military exercises increased from 2016 to 2023. Data has been compiled from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), security assessment reports, and official military sources.

Violent incidents in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) declined sharply as the frequency of military exercises increased from 2016 to 2023. Data has been compiled from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), security assessment reports, and official military sources.

That’s why these operations have to happen again along the border region. It’s not about flexing muscles for the sake of it. It’s about denying militants the breathing space they use to plan the next wave of attacks.

None of this is new. KP and the tribal districts have seen a string of major operations over the years: Rah-e-Rast in Swat, Zarb-e-Azb in North Waziristan and Radd-ul-Fasaad across the country. Each time, the army went in with heavy ground and air firepower. Each time, the goal was the same: wipe out terrorist bases and bring the area back under government control.

Those operations were not perfect, but without them, militants would still be running parallel governments in parts of erstwhile FATA. That history matters because it shows that force, when sustained, makes space for normal life to return.

That said, groups like Amnesty International keep raising an important point that military strength alone cannot ignore civilian lives. Their latest report calls for more restraint, so ordinary families don’t end up paying the heaviest price. And they’re right. Every time a house is destroyed, or a family is displaced, resentment builds.

So, the balance is tricky. It’s not easy to pull punches against people who are planting bombs, but you also can’t alienate the very population whose cooperation you need to keep peace once the soldiers leave. Relief efforts, rebuilding homes, reopening schools – those must follow close behind the operations.

Here’s another thing often lost in the security debates: KP is lagging on development. The province ranks lower than Punjab or Sindh on human development indicators. That’s no surprise given how much of its recent history has been tied up in conflict. Schools were shut, health facilities were wrecked, investment dried up.

For KP to move forward, security must come first. Investors, aid organisations, and even local entrepreneurs won’t put down roots in a place where militants can still strike at will. So, while military operations might feel like a stopgap, they lay the foundation for things like education reform, jobs, and healthcare improvements. Without peace, all those other goals remain stuck on paper.

It’s easy to see KP’s troubles as local, but they spill over. Militants based in the province have carried out attacks in big cities like Lahore and Karachi. KP is also Pakistan’s link to Afghanistan and Central Asia, so instability here undermines regional trade plans and national security all at once.

That’s why operations like Sarbakaf aren’t just about Bajaur or even KP. They’re about Pakistan’s ability to protect itself. At the end of the day, the debate boils down to this: people want peace, but peace doesn’t come cheap. The use of force may sometimes seem unpleasant and controversial. Yet history shows it’s the only thing that has pushed militants back enough for normal life to resume.

That doesn’t mean force is the only answer. Governance must improve, the justice system must deliver, and development has to catch up. But without military strength, all those efforts are vulnerable to being derailed by another wave of violence.

So, when Chief Minister Gandapur calls for unity, he isn’t exaggerating. The army can fight, but the people and the institutions must hold the ground that’s cleared. Otherwise, it’s a cycle with no end.