Pakistan’s border closures aim to protect national security as Afghan militants continue using Afghan soil to attack across the frontier.

Maaz Khan

PESHAWAR: Shortly after dawn in Kabul, the streets around the wholesale markets begin to stir. Shopkeepers lift metal shutters, traders gather for tea, and truck drivers scroll endlessly through their phones, waiting for updates that never seem to arrive.

The goods they are waiting for — medicine, fuel, cement, fruits — are not far away. Most are stuck across the border, held up by a decision taken hundreds of kilometres south.

As of January 16, 2026, Pakistan’s closure of key Afghan transit and trade routes has entered its eighty-third day. Implemented on October 12, 2025, the restrictions were imposed on security grounds. But for Afghanistan, the fallout has evolved into something far larger than a temporary disruption. What is unfolding is a slow-moving economic shock — largely unnoticed outside the region, yet deeply destabilising inside the country.

This is not a crisis marked by explosions or dramatic collapse. It is quieter, incremental, and relentless. Containers pile up. Markets thin out. Prices creep upward. Livelihoods disappear. And for a landlocked country already struggling under sanctions, poverty, and political isolation, the margin for survival grows thinner by the day.

A Lifeline Severed

Afghanistan’s geography has always defined its economy. As a landlocked country, it depends heavily on neighbouring states for access to global markets. Among all available routes, Pakistan has long been the most practical: the shortest distance, the lowest cost, and the most developed infrastructure.

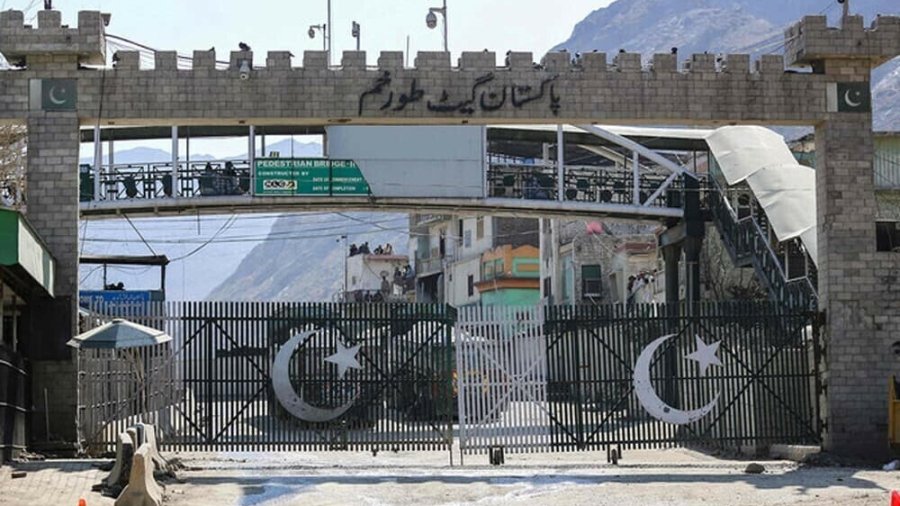

For decades, Afghan trade flowed through Karachi port and across the land crossings at Torkham and Chaman. Through these corridors, Afghanistan exported its signature goods — dry fruits, saffron, carpets, coal — and imported essentials ranging from food and fuel to medicines and industrial inputs. The system was imperfect, often politicised, and periodically disrupted, but it functioned.

That system is now largely frozen.

According to figures shared by the Afghanistan Chamber of Commerce and Investment, bilateral trade between Pakistan and Afghanistan has fallen by nearly 45 per cent since the closures began. Afghan traders estimate daily losses of $1.8 to $2 million, pushing the cumulative damage to $400–500 million in just over two months.

More than 11,000 cargo containers, many carrying perishable or time-sensitive goods, remain stuck at Pakistani ports and border points. Their total value runs into several billion dollars, tying up capital, paralysing businesses, and triggering disputes between traders, insurers, and banks.

“This is not just a slowdown,” says an Afghan logistics operator in Kabul who requested anonymity. “It is a near-total paralysis of the supply chain.”

Exports in Freefall

The impact is most visible in Afghanistan’s already fragile export sector.

For years, Afghan traders worked to establish markets for products that carried both economic and cultural value: handwoven carpets, saffron cultivated in Herat, dried fruits from Kandahar and Badakhshan, coal from northern provinces. These exports generated much-needed foreign exchange in an economy starved of liquidity.

Now, many of those goods are either not moving at all or are being rerouted through far longer and more expensive alternatives.

“International buyers do not wait,” says a carpet exporter in Herat. “If Afghan shipments are delayed or prices rise, they switch to Iran, Turkey, or Central Asia. Once you lose a buyer, you rarely get them back.”

The closures have compounded an existing decline. According to World Bank data, Afghanistan’s coal exports fell by 64 per cent in 2024, while overall exports declined by 12 per cent. Traders say the current blockade-like conditions risk wiping out what remains of Afghanistan’s export credibility.

For a country with limited production capacity and almost no access to international banking, the loss of export earnings carries consequences far beyond individual businesses.

When Shortages Reach Homes

If export losses threaten Afghanistan’s future, import disruptions are harming its present.

Afghanistan depends heavily on Pakistan for critical imports, particularly:

• Medicines and medical supplies

• Wheat and other staple foods

• Fuel and cooking gas

• Industrial raw materials

With transit routes restricted, shortages have begun to surface across Afghan cities. Pharmacies report dwindling stocks of essential medicines. Fuel prices have surged, raising transport costs and pushing up food prices. In lower-income neighbourhoods, families are already cutting meals or turning to cheaper, less nutritious alternatives.

“This is becoming a humanitarian issue,” said a Kabul-based aid worker. “When medicines don’t arrive and food prices rise, it is the poorest who absorb the shock.”

The timing is especially severe. Winter has tightened its grip, energy demand is rising, and household incomes are falling. Unlike previous trade disruptions, there is little cushion left.

The Illusion of Alternatives

In response to the closures, Afghan authorities and traders have accelerated efforts to shift trade through Iran and Central Asia. On paper, diversification appears sensible. In practice, it has exposed Afghanistan’s structural vulnerability.

Iran, itself under heavy sanctions and economic strain, lacks the capacity to absorb Afghanistan’s sudden transit needs. Congestion at ports, currency instability, and regulatory hurdles have made the route unreliable and costly.

Central Asian corridors present a different set of problems: underdeveloped rail and road infrastructure, fragmented customs systems, and higher transit fees. For many Afghan traders, these routes add weeks and thousands of dollars in additional costs.

“These are not alternatives,” said a regional trade expert based in Islamabad. “They are emergency detours — slower, costlier, and unsustainable at scale.”

Despite diplomatic messaging about regional connectivity, geography remains unforgiving.

The Broader Economic Shock

Beyond trade statistics, the closures are sending shockwaves through Afghanistan’s wider economy.

Economists estimate that when indirect losses — such as reduced tax revenue, job losses, currency pressure, and stalled investment — are factored in, Afghanistan may have already suffered $6–7 billion in cumulative economic damage over the past 75 days.

The symptoms are increasingly visible:

• Rising inflation across urban markets

• Sustained pressure on the Afghan currency

• Declining state revenues

• Closure of small and medium enterprises

• Growing unemployment and underemployment

For a country with limited fiscal tools and no access to international financial systems, absorbing such shocks is exceptionally difficult.

“This economy was already operating on survival mode,” says an Afghan economist. “The closures push it closer to systemic failure.”

A Crisis with Regional Consequences

While Afghanistan’s economic distress is deepening, its repercussions are increasingly contained within Afghan territory, reflecting Pakistan’s significantly tightened border management over the past several years.

Security analysts note that Pakistan’s completion of extensive border fencing, enhanced surveillance, and stricter customs enforcement have sharply reduced illicit cross-border movement. Smuggling networks that once thrived along the frontier have been largely dismantled, and undocumented crossings have dropped to a fraction of previous levels.

“Unlike the past, Pakistan now has the infrastructure and enforcement capacity to insulate itself from economic spillovers originating across the border,” observes Ghulam Dastageer, a Peshawar-based journalist who has extensively worked on border fencing. “The fencing has fundamentally altered cross-border dynamics.”

From Islamabad’s perspective, the closure of trade routes is therefore framed not as a destabilising act, but as a security-driven measure taken within a controlled border environment. With illicit trade curtailed and border permeability reduced, Pakistan faces minimal internal economic or security fallout from Afghanistan’s current downturn.

Historically, Pakistan–Afghanistan trade disruptions did carry regional consequences. What distinguishes the present episode is that Pakistan has already absorbed those risks through long-term border management investments, even as Afghanistan — now facing unprecedented economic fragility — bears the overwhelming cost of the disruption.

Geography, Again

At its core, the crisis underscores a simple reality: geography is not negotiable.

Afghanistan’s economic survival remains deeply tied to access through Pakistan. No amount of political rhetoric can erase that dependency in the short or medium term. Traders on both sides of the border warn that repeated closures erode trust, discourage investment, and push commerce into informal channels.

“Once trade becomes unpredictable, businesses stop planning,” says a Pakistani freight forwarder involved in Afghan transit trade. “They either shut down or move underground.”

Waiting for Relief

As winter deepens, the cost of the closures continues to rise — measured not just in dollars, but in diminished lives. In Kabul, shopkeepers shorten business hours to save fuel. In provincial towns, farmers struggle to sell produce. Across the country, families stretch shrinking incomes to cover rising prices.

For many Afghans, the crisis is no longer abstract or geopolitical. It is immediate and personal.

If the current restrictions persist, economists warn Afghanistan risks sliding into a prolonged economic contraction — one whose effects could last generations.

As thousands of containers remain idle and markets continue to thin, a stark question hangs over the region: How long can a landlocked country endure with its lifelines cut?

Security Deadlock: The TTP Factor

Pakistan argues that the current economic disruption cannot be separated from Afghanistan’s failure to act against Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) militants operating from Afghan territory. Pakistan has shared a credible dossier with the Afghan authorities establishing that these groups continue to use Afghan soil to plan and launch attacks inside Pakistan, despite repeated diplomatic engagements and assurances from Kabul.

From Islamabad’s standpoint, the suspension of trade routes reflects a security imperative rather than economic pressure. “No country can sustain open trade when armed groups are allowed to threaten its citizens from across the border,” says a Pakistani security official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Analysts note that Afghanistan’s continued denial or inaction has narrowed its economic and diplomatic space. Pakistan maintains that regional trade and stability are inseparable from credible counterterrorism commitments. Without recalibrating its internal security posture and external policies — particularly towards Pakistan—Afghanistan risks prolonged isolation and deeper economic decline.

The impasse, observers say, leaves Kabul facing a clear choice: redesign policies to restore regional confidence, or slide further into economic obscurity driven by unresolved security concerns.