Dr. Sahibzada Muhamma Usman

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has seen too many cycles of violence. The province, especially places like Bajaur near the Afghan border, has been caught in the middle of insurgency for years. Every time there is a lull, groups like the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) find ways to regroup. That’s why the State keeps going back to the same conclusion: without military strength, there’s no chance of lasting stability here.

Take account of the recent Operation Sarbakaf. Launched in August 2025, it is the latest reminder that the fight is still very real. Security forces, backed by artillery and helicopter gunships, went after militant hideouts in Bajaur. Also, reports say several militants were killed and captured. It was not a token of force; it was a clear attempt to dismantle a network that’s been haunting the region for years.

Notably, Bajaur’s geography makes it a natural entry point for militants’ crossing over from Afghanistan. The mountains and difficult terrain have given them cover for decades. So, when the army moves in with heavy weapons, it is not overkill. It’s a response to how deeply entrenched these groups are.

Of course, these operations come with a human cost. Some tribal elders have voiced worries about people being displaced again, which is fair. The memory of entire communities uprooted during earlier operations is still fresh. Nobody wants to relive that.

But there’s another side to it. KP’s Chief Minister Ali Amin Gandapur recently said, “The public and all institutions must work together to establish peace. Our future depends on it.” That’s the truth. The military can clear an area, but unless people and institutions back the effort, the militants just slip back in.

One of the toughest parts of this whole problem is that the TTP isn’t operating in a vacuum. They’ve got safe havens across the border in Afghanistan. Studies published this year point out how these sanctuaries are being used to regroup and plan attacks inside Pakistan. So even if Bajaur is cleared, the threat isn’t gone.

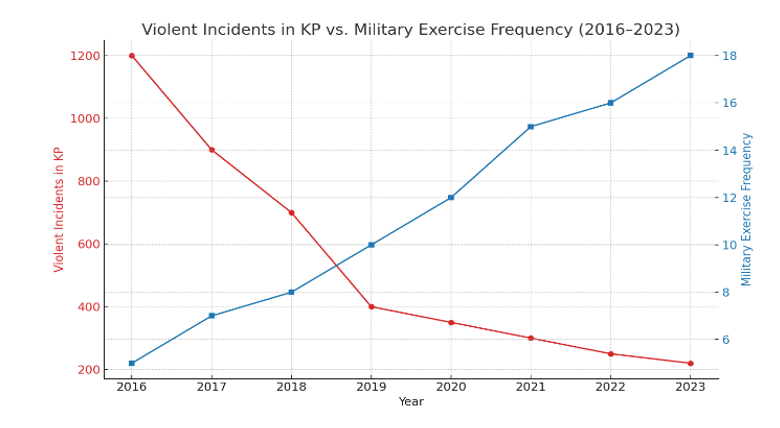

Notably, no peace without military strength in KP is possible. This is reflected in the graph below, which is synthesised from multiple credible resources.

Figure 1

Violent incidents in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) declined sharply as the frequency of military exercises increased from 2016 to 2023. Data has been compiled from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), security assessment reports, and official military sources.

Violent incidents in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) declined sharply as the frequency of military exercises increased from 2016 to 2023. Data has been compiled from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), security assessment reports, and official military sources.

That’s why these operations have to happen again along the border region. It’s not about flexing muscles for the sake of it. It’s about denying militants the breathing space they use to plan the next wave of attacks.

None of this is new. KP and the tribal districts have seen a string of major operations over the years: Rah-e-Rast in Swat, Zarb-e-Azb in North Waziristan and Radd-ul-Fasaad across the country. Each time, the army went in with heavy ground and air firepower. Each time, the goal was the same: wipe out terrorist bases and bring the area back under government control.

Those operations were not perfect, but without them, militants would still be running parallel governments in parts of erstwhile FATA. That history matters because it shows that force, when sustained, makes space for normal life to return.

That said, groups like Amnesty International keep raising an important point that military strength alone cannot ignore civilian lives. Their latest report calls for more restraint, so ordinary families don’t end up paying the heaviest price. And they’re right. Every time a house is destroyed, or a family is displaced, resentment builds.

So, the balance is tricky. It’s not easy to pull punches against people who are planting bombs, but you also can’t alienate the very population whose cooperation you need to keep peace once the soldiers leave. Relief efforts, rebuilding homes, reopening schools – those must follow close behind the operations.

Here’s another thing often lost in the security debates: KP is lagging on development. The province ranks lower than Punjab or Sindh on human development indicators. That’s no surprise given how much of its recent history has been tied up in conflict. Schools were shut, health facilities were wrecked, investment dried up.

For KP to move forward, security must come first. Investors, aid organisations, and even local entrepreneurs won’t put down roots in a place where militants can still strike at will. So, while military operations might feel like a stopgap, they lay the foundation for things like education reform, jobs, and healthcare improvements. Without peace, all those other goals remain stuck on paper.

It’s easy to see KP’s troubles as local, but they spill over. Militants based in the province have carried out attacks in big cities like Lahore and Karachi. KP is also Pakistan’s link to Afghanistan and Central Asia, so instability here undermines regional trade plans and national security all at once.

That’s why operations like Sarbakaf aren’t just about Bajaur or even KP. They’re about Pakistan’s ability to protect itself. At the end of the day, the debate boils down to this: people want peace, but peace doesn’t come cheap. The use of force may sometimes seem unpleasant and controversial. Yet history shows it’s the only thing that has pushed militants back enough for normal life to resume.

That doesn’t mean force is the only answer. Governance must improve, the justice system must deliver, and development has to catch up. But without military strength, all those efforts are vulnerable to being derailed by another wave of violence.

So, when Chief Minister Gandapur calls for unity, he isn’t exaggerating. The army can fight, but the people and the institutions must hold the ground that’s cleared. Otherwise, it’s a cycle with no end.